In Brief

Massive Earthquake Could Reshape Turkish and Syrian Politics

Turkish President Erdogan and Syrian President Assad could see opportunities to extend their rules in the disaster that has killed tens of thousands and pushed relief systems to their limits.

What was the impact of last week’s powerful earthquake in Turkey and Syria?

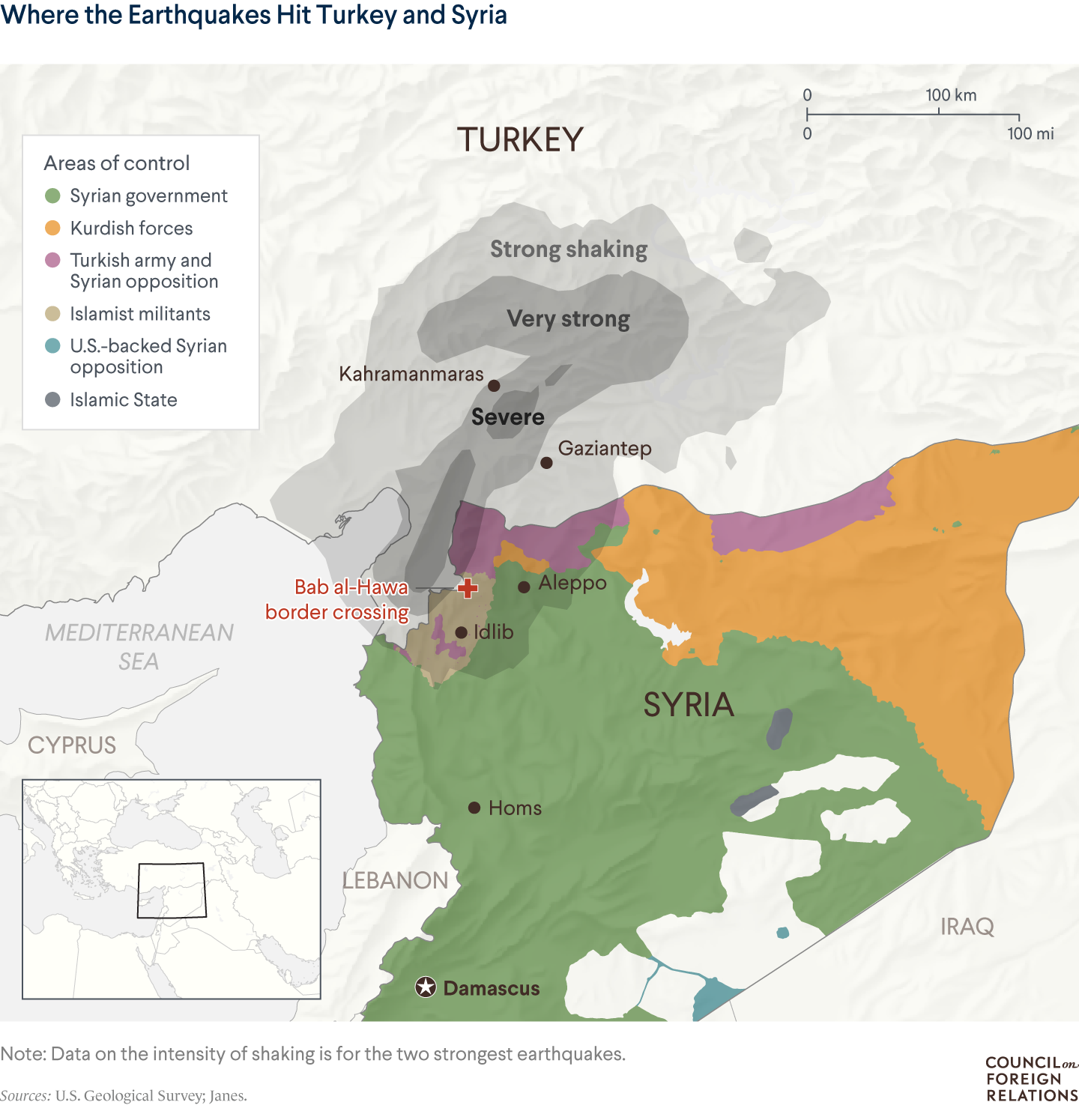

The combined death toll stands at more than thirty-six thousand at time of writing, but it is too early to ascertain the full impact. In Syria, the earthquake and its aftershocks hit Idlib, the area most ravaged by the country’s civil war and one of its last rebel-held territories. This adds more misery especially because the regime will prioritize its own interests at the expense of the affected populations. Paradoxically, Turkey, which sits on the same geological fault lines as Syria, is Damascus’s primary antagonist in the very area hit by the earthquake. However, Turkey has of late been maneuvering to patch up its relations with Syria. The shared disaster could provide the necessary pretext to speed that process up.

Outside nations and international organizations have a crucial role to play in relief and recovery, especially in Syria. Is there a danger of domestic tensions jeopardizing their response?

More on:

Idlib has borne the brunt of the disaster. So far, with UN aid limited to a single border crossing, the flow of relief supplies to Syria’s affected regions has been meager or nonexistent. The White Helmets, the main nongovernmental organization (NGO) operating in the area, have accused the United Nations of not providing enough help. Bashar al-Assad’s regime will be tempted to use this disaster to reunite the country under his control; he has already indicated that he wants all relief to be coordinated with the central government in Damascus, despite the fact that he does not control the most afflicted populations. To facilitate relief efforts, regime and World Health Organization officials are holding discussions on reopening a border crossing closed since 2013.

Comparisons have been made to Turkey’s disastrous 1999 earthquake in terms of poor preparedness. Could Turkey have minimized casualties in this disaster?

Despite repeated assurances that the country had learned its lessons from the 1999 earthquake, the scale of the current calamity indicates that authorities were quite lackadaisical in their preparations. The billions of Turkish liras collected by the government through a special earthquake tax were clearly not used to strengthen the affected region’s infrastructure or the capabilities of the country’s emergency response system. In fact, the budget of the Disaster and Emergency Management Authority (AFAD), the primary rescue organization, was reduced by 33 percent [article in Turkish] in the 2023 national budget.

Worse was the 2018 decision to push through an amnesty legalizing the status of thousands of buildings that had been unlawfully built without proper documentation and inspections. All residents had to do was pay a fine that simply boosted state coffers. In fact, in a 2019 visit to Kahramanmaras, the epicenter of the earthquake, President Recep Tayyip Erdogan proudly declared [article in Turkish] that with the amnesty, the government had “solved the problem of 144,556 Maras citizens alone.” In effect, for him the “problem” was not that citizens lived in shoddily constructed, precarious abodes, it was their inability to acquire ownership documents for buildings that had been labeled “illegal.” By a simple stroke of the pen, these constructions were effectively made safe. Clearly, the “earthquake” did not seem to agree.

Turkish authorities’ relief response has been poorly coordinated and late in arriving; there still are numerous afflicted areas waiting for supplies and volunteers. By contrast, civil society’s response has been admirable: volunteers and aid parcels from every part of the country have been pouring in as locals have taken the initiative to rescue victims. As University of Kurdistan Hewler Associate Professor Arzu Yilmaz simply summarized [article in Turkish], “There is no state but there is a people.”

How has Erdogan responded so far, and what ramifications could the quake have for Turkey’s May 14 general elections?

The immensity of the calamity has clearly shaken Erdogan. It took him some time to appear in public, and much of his pronouncements and travels through the afflicted areas have focused on protecting the state and his administration. Predictably, he started looking for “the culpable,” i.e., shoddy builders and looters he can accuse and thus deflect away blame.

More on:

It is difficult to imagine that the region can recover sufficiently to conduct elections. It is not just the destruction of property and loss of life that is challenging, but also the fact that many residents are likely to disperse throughout Turkey in search of shelter with family and friends. Of the four provinces afflicted—Adiyaman, Gaziantep, Hatay, and Kahramanmaras—only in Hatay did Erdogan’s Justice and Development Party (AKP) not win a majority of the votes in the 2018 parliamentary elections. (It was still the number one party.) These are his votes to lose in the next contest.

The problem facing Erdogan is that he can only postpone the elections to June 18, the absolute last possible date. An extra month will not significantly improve conditions on the ground. The constitution states that only during a state of war can elections be deferred, for up to a year. Yet, Erdogan has hinted that these elections could take place a year from now along with scheduled municipal ones. He has complete control of the state and society’s institutions, especially the judiciary. Therefore, it could be possible for him to concoct a solution in his favor.

However, it is difficult to assess the course of this earthquake’s political aftershocks; there will be many more to come and they are unlikely to be linear and predictable. With myriad economic troubles confronting the country, Erdogan was already in the midst of the toughest reelection fight of his life before the quake, though he appeared to be holding his ground by manipulating the legal system and eliminating opponents, politicians, and parties. The earthquake will certainly and dramatically upend voters’ calculations; his political skills notwithstanding, Erdogan is facing an inexorable tsunami of discontent.

Will Merrow and Michael Bricknell created the graphic for this article.

Online Store

Online Store